Implications Of NI

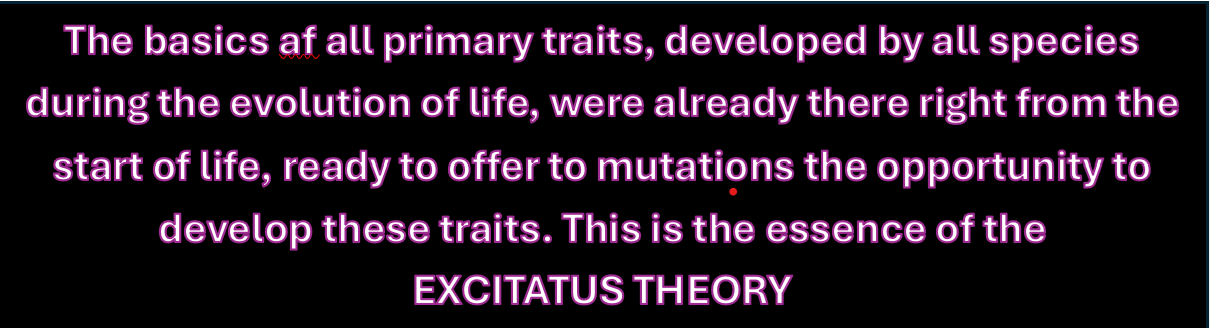

There is question unanswered. If a region of DNA or a combination of regions of DNA are capable to introduce in time a new trait in which ‘a new species to be’ will find its evolutionary focus, then is the genetic basis of this trait already there and just waiting to be activated by a mutation or a couple of mutations? Or could this mutation or these mutations have such an impact that this region or these regions make such a radical change that this results in a complete new trait based on a complete new code and protein? Think for instance about flying. Does the capability of flying originate from small steps each in the form of changing DNA regions (according to the Evolution Theory even again and again by coincidence) or from the activation of the DNA regions where this ‘hidden’ feature of flying was already (latent) present? Maybe only the basics. Or could it be a combination of both?

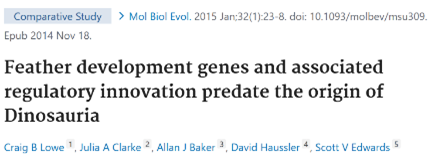

A study (_Feather Development Genes and Associated Regulatory Innovation Predate the Origin of Dinosauria_ by Craig B. Lowe at al.) published in the journal ‘Molecular Biology and Evolution’ showed that the DNA code that birds share and gives them their feathers has already been in DNA for hundreds of millions of years before anything resembling a feather appeared on a species.

About 100 million years before the first bird flew, almost the complete genetic code to make a feather was already present in the DNA of the ancestors of birds. This study also indicate that the shrinking of the body size and growing of their limbs made it possible for birds to get into the air (‘survival of an internal fit’). By the way: also humans carry the feather code. The reason that we don’t have feathers is that genes can do different job in relation to the production of proteins. So yes a switch could also results in feathers on humans.

So what can be concluded on the basis of these findings? That a switch from one focused trait to another, as presented in the NI theory, and qualified as a revolutionary evolution, can be a realistic scenario, because the basic DNA conditions needed to make the new trait can already be present, so can be switched on, can become dominant and evolve from there on. And also a switch from a none focused trait to a focused trait is an option. At least if the outcome of the mentioned research can be generalized. And so there is in that situation no need for a very slow evolutionary process during which feathers develop thanks to the ‘law’ of the ‘survival of the fittest’.

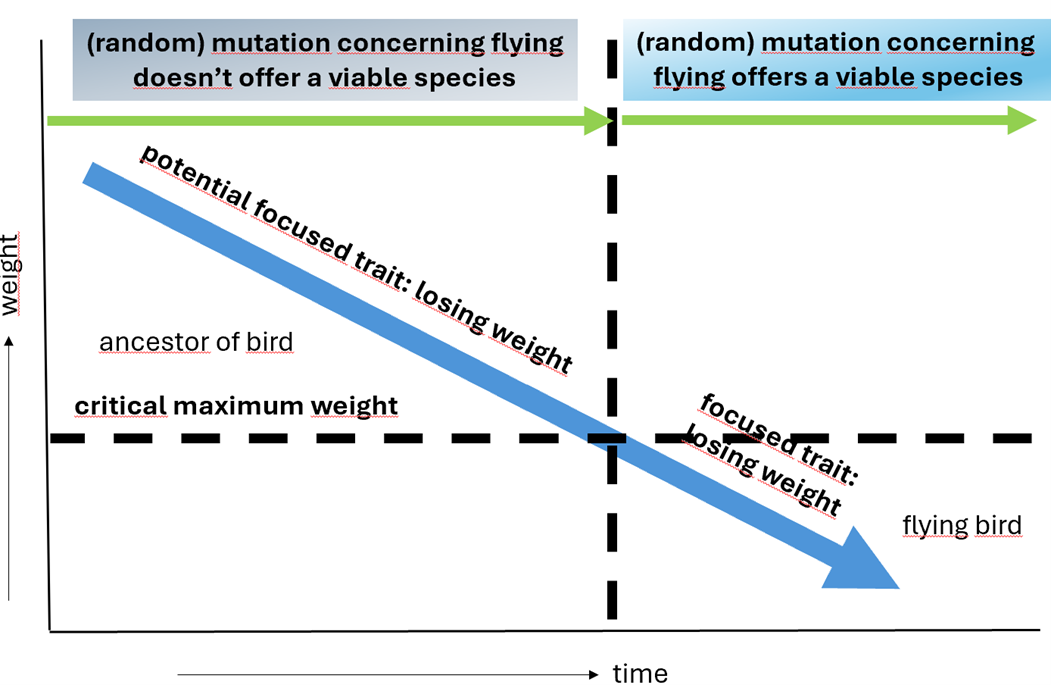

You may say: ok, that could be true but what about the process of a shrinking body and growing arms over a long period? Though the cited article does not go into that, one can imagine that there are also a DNA sequence and genes for this effect. And that they were already present long before the first bird would fly. So switching on of these genes at a certain moment was enough to start the development of the species of birds. So the combination, at probably two different moments in evolution, of two revolutionary evolutions could have done the trick: making the production of feathers a focused trait and also making the shrinking of the body and lengthening of the arms a second focused trait. There is even a more simple scenario possible. The shrinking of the body and/or the growing of the arms could have been the result of a random evolution that appeared to be essential to clear the way to make the directional evolution concerning the development of feathers finally (after being there for 100 million years already) viable.

Or in NI-language: the outcome of the ‘survival of the fittest’ became positive because the obstructive traits of weight and short arms became less limiting so the potential focused trait of flying could take its chance to become a focused trait (was no longer only a part of the genotype in the context of a higher susceptibility). One can also imagine a process the other way around: losing weight was the focused trait and the weight reduction gave the, so far not usable trait of developing wings, the opportunity to offer a better or even a best fit. And gave the opportunity to the birds to finally get off of the ground. Further on I will show you that this are indeed plausible scenarios.

Any other examples of obstructive traits blocking or limiting the use of a focused trait? Earlier I already mentioned the latent capability of humans to have a hibernation. Another one? Ok this becomes a bit more tricky. I would not surprise me if there are one or more traits that put a limit to our ways of thinking and our fantasy. If you miss that obstructive trait on the one hand you could get a trait that offers you the capability to imagine and realize things other people can’t, but on the other hand life can become quite difficult to live. I am talking about for example Vincent van Gogh, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Jim Morrison and Amy Winehouse. People who were unique and were capable of incomparable achievements. But on the other hand life was sometimes very hard for them, not seldomly resulting in the abuse of drugs and alcohol. The brains of Einstein only weighted 1.230 gram; significantly less than the average weight of about 1.400 gram of the brains of a grown up man.

I think there is even another example, if we are talking about mankind. Hardcore criminals do also miss a trait that should have limited their criminal behaviour and the boldness of their actions. So special talents may not be the result of something extra but of something less. Obstructive traits may not only limit the benefits of a focused trait but also their downturns.

The origin of birds as a result of the existence of the feather-code in DNA long before the origin of the first bird, and so giving the chance to completely develop this trait at the right moment in time, is way more plausible than the theory that a bird evolved out of a reptile by hundreds of coincidental small steps. It is completely unclear to me how each of this tinny steps, say for instance a skin changing from 2 feather like hairs per square inch to four of them, could ever implicate a better fit and so reduce the animals with just 2 of these feather like hairs per square inch to losers with none or with less offspring as a result. So the origin of birds can by explained with NI, or to be exact on the basis of revolutionary evolution, where the origin of the huge variety of birds can be explained as an evolutionary process on the basis of random and/or directional mutations.

To give another example.

Scenario 1: The first move from water to land started by some curious fishes that moved out of water and consequently died. And then at a certain moment one of the fishes acquired by coincidence the capability to survive out of the water for a short period of time. And by another coincidence (coincidence x coincidence) also this fish tried, despite of the death of its ancestors, to go out of the water, and so didn’t die. And this new fit started from there its evolution.

Scenario 2: A fish acquired (by switching on a certain DNA-region) the capability to survive out of the water for a short period of time and by coincidence discovered (coincidence x coincidence) this new trait and made use of it to catch prey that was out of reach for his a her colleagues. And this new fit started from there on its evolution.

Scenario 3: Due to a revolutionary evolution from time to time some fishes acquired (by switching on a certain DNA-region) the capability to survive out of the water for a short period of time. For one or a few species of fish this new trait could be fitted in. This was an (inheritable) focused trait but none of the fishes with this mutation was aware of it. So the group of fishes with this trait is growing steadily. At one moment one of them by coincidence (coincidence x < coincidence) discovered this new trait and made use of it to catch prey that was out of reach for his a her colleagues. And this new fit started from there on its evolution.

What do you think is the most plausible scenario? The first one, the second or the last?

My opinion is (from most likely to less likely): 3; 2; 1.

According to NI the main evolutionary moments concerning the phenotype starts with the ‘discovery’ of the opportunities of a new trait instead of the ‘discovery’ of a new opportunity and over and over trying to grasp it without the needed trait, so failing every time. Till suddenly a coincidental mutation offers one individual the chance to grasp this opportunity without failing. Are you going through a wall, if there is a door you can open, because you discover by coincidence that a couple of you have the right key, or are you and your friends are going to smash your head into the wall and door without the right key over and over again, with as only result a blooding head? Till someone of you maybe will find at one moment by coincidence the right key?

There are clear reasons to skip the Evolution Theory in this situation and go for NI, at least if we are talking about the first steps of this process. Neil Shubin, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Chicago, told ‘Live Science’ that lungs were already around long before the sea-to-land transition happened. Lungs are actually surprisingly primitive in evolution. When our fishy ancestors still lived underwater, they already had lungs in addition to gills. Similarly, scientists think our fish ancestors evolved arms to move around on the ocean floor, which later came in handy for finding food and moving around on land. So first the internal processes took place, which brought new possibilities and only after that evolutionary step, when this new trait was discovered, was useful and was used, ‘survival of the fittest’ could claim its role. A new fit is not the result of a random trying if by coincidence a trait has developed that will give a positive outcome but by discovering by coincidence this new trait.

The basics of a trait (DNA-region) are not only there long before a species starts to make use of it, but are also there, again maybe just in its basic form, long after that this trait has become redundant. Human embryos have a fishy physical trait (called pharyngeal arches) that resemble gills, but we don't use them to breathe. They are considered a relic of early gills. Throughout embryonic development those arches become parts of the jaw, throat and ears. I wonder if this is really a relic. Could it not be the result of a genetic condition that is present in all DNA right from the start? And is there to stay? Maybe mankind will at one moment in the future be able to move back to the water if this hidden trait becomes activated again and maybe even becomes a (potential) focused trait. That would be something! Maybe to survive global warming or to life on an exoplanet with no land and only sea.

So in my opinion the basics of fundamental traits - like surviving in water, moving on land, flying in the air – are there right from the start and will genetically stay there even if these traits have never been used or only used by ancestors a long time ago. This also implicates that if a species has some remnants of a trait, maybe only as an embryo, this doesn’t present an evidence that an extinct species, which had this trait, must have been an ancestor of the first mentioned species.

The trait, in which a ‘species to be’ will directionally evolve and that identifies this new species, is not by definition the result of a slow evolution starting with a minimal change of a trait of the ancestor of this new species, but it can be the result of a genetic process that switches on the region in DNA of the ancestor that makes this ‘new’ trait available and inheritable and so a (potential) focused trait for this ‘species to be’.

I call that the ‘Excitatus Theory’ (opposite or next to the Evolution Theory).

Are there more arguments to support this theory that the basics of all fundamental traits of ‘species to come’ could already have been in DNA from the very start? Problem one is of course that we have no insight in what the DNA of the first living cells looked like. The oldest DNA, that could be investigated, was only 12 million years old. There are all kinds of publications in which is written that the first DNA was simple and only coded the basic traits to survive, but in fact nobody knows and this is also not more than a theory. One could say, look at the DNA of today’s one cell species, but there are clear indications that they are not representatives of the first one cell creatures on earth.

This is not just a guess. There are clear indications that some genes, that are essential in many species nowadays, are indeed present in DNA for a very long time and also have played their role in the existence of many ancient species. For instance there is the Distal-less gene. the earliest known gene specifically expressed in developing insect limbs. This gene also played a role in the development of the fins of fish, the wings of chicken, the parapodia of certain marine worms and the tube feet of sea urchins. The conclusion was that these gene had to be more than 600 million years old because in that period their common ancestor lived. According to my theory this gene is indeed very old, not because of this (possible) common ancestor, but because it is one of the genes that basically was already there right from the start.

Biochemists have established that some proteins, that are essential for life, are exactly the same in all species, animals and plants alike. The genes that code these proteins didn’t mutate, because that would evidently lead to death.

Some more facts. There are more than 500 amino acids in nature but only 20 (+2 for some special species) of them are present in the proteins of living species. The genetic code (the "translation table" according to which DNA information is translated into amino acids, and hence into proteins) is nearly identical for all known lifeforms, from bacteria to animals and plants. So about the fact that the DNA regions that code the basic traits - to life, to digest, to reproduce and so on – didn’t mutate or hardly mutated, there is no discussion. But how about other basic features like feathers, hair, lungs, ears and so on?

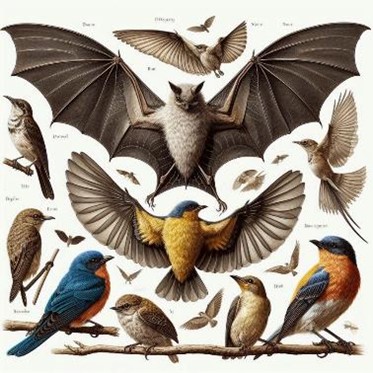

An interesting phenomenon in this respect is so called ‘convergent evolution’. This means the independent evolution of similar features in species during different periods or epochs in time. Convergent evolution creates analogous structures that have similar form or function but were not present in the last common ancestors of those groups (not in their phenotype but maybe still in their genotype!). The recurrent evolution of flight is generally seen as a classic example, as flying insects, birds, pterosaurs and bats have independently evolved the useful capacity of flight. It is believed that convergent evolution may appear when different species live in similar ways and/or a similar environment, and so face the same environmental factors. When occupying similar ecological niches. Birds and bats have independently evolved their own means of powered flight. Their wings differ substantially in construction. But still there are some remarkable resemblances. For instance both share a high concentration of cerebrosides in the skin of their wings. This improves skin flexibility, a trait useful for flying animals. Opposite to this, mankind have developed many more principles of flying in a much shorter timespan (heated balloon, zeppelin, rocket, wings plus propellers/yet engines, helicopter) but nature clearly sticks to wings.

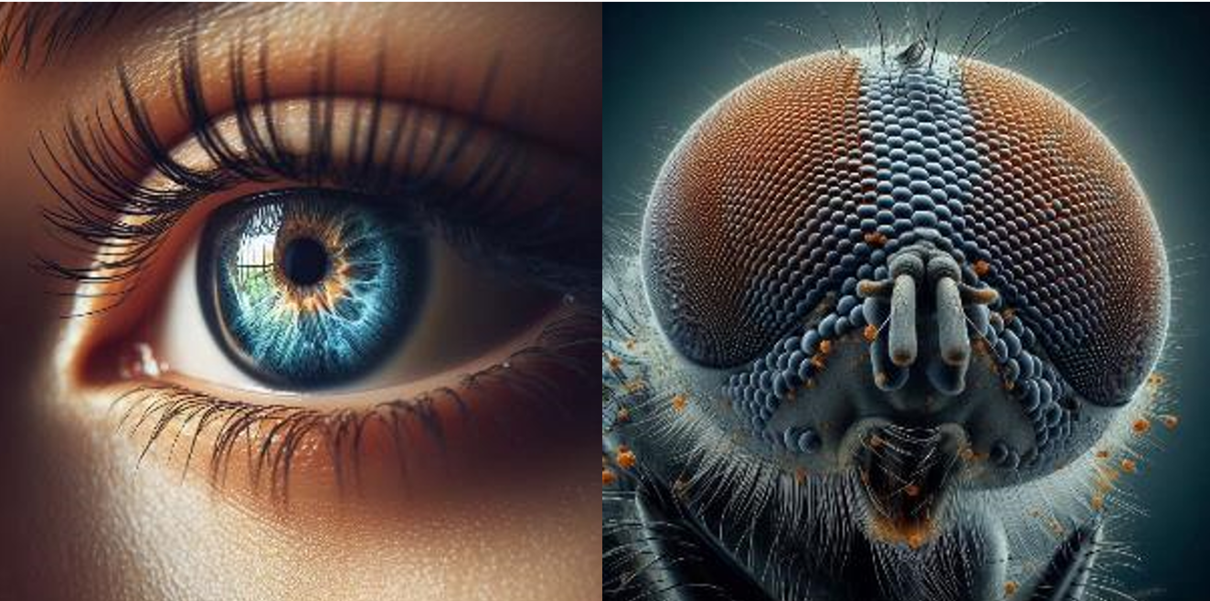

A second example that is often mentioned, if talking about convergent evolution, concerns the eyes of vertebrates and of cephalopods. They developed independently and are wired differently. Their last common ancestor had at most a simple photoreceptive spot, but a range of processes (that is the theory) led to the progressive refinement of camera eyes.

Here again there is one essential gene with the name pax-6. It plays a vital role for forming the eyes of fruit flies, mice, humans and squid. It is believed that eyes have arisen in animals at least 40 times. It is generally believed that they all evolved from a common ancestor. And that it concerns an ancient gene that had been conserved through millions of years of evolution (so was apparently switched off) to create dissimilar structures (the eyes of the mentioned species have different structures) for similar functions. According to the Excitatus Theory I have another opinion and more simple explanation: this gene didn’t start with this common ancestor (because why should it start there?) but the basics of this gene, and so the capability to develop eyes, was there right from the start.

How can the Evolution Theory explain that the same body parts evolve at least 40 times independent of each other? And how can ET explain that in all these animals the function is the same (be able to see) but the structure is different? According to Excitatus Theory this has to do with a trait which was and is there all the time right from the start. In every animal eyes can offer the ‘survival of the fittest’ but they had to develop in such a way, that for the concerning species it gave a viable outcome in the combination with its other relevant traits, which were different in every of these species. So it is realistic to assume that the more a trait is beneficial, the more versions there will evolve of this trait.

Recently 27 new species have been discovered in the Alto Mayo Landscape, spanning the Andes to the Amazon and including the Alto Mayo Protected Forest. One of these species is an amphibious mouse with webbed toes. What is more likely? That ducks and these mice have a common ancestor or that the genes, capable of producing these kind of toes, are present in all DNA and that the ‘survival of the fittest’ rewards animals swimming on the surface of water with this trait, if (by coincidence) this gene is switched on?

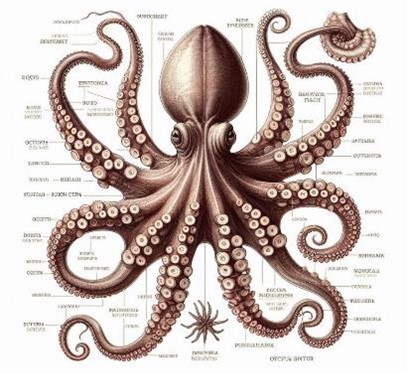

Possibly there is a new example in the making. Professor Tim Coulson of the University of Oxford, one of the world’s leading zoologists and biologists, states that octopuses are primed to become the dominant force on earth should humanity die out. According to him octopuses possess the physical and mental attributes necessary to evolve into the next civilization-building species. Their dexterity, curiosity, ability to communicate with each other, and supreme intelligence mean that they could create complex tools to build an Atlantis-like civilization underwater. The professor says they could, over millions of years, develop their own methods of hunting on land in much the same way as humans have done at sea. This could include SCUBA-like breathing gear. “_Their ability to solve complex problems, manipulate objects, and even camouflage themselves with stunning precision suggests that, given the right environmental conditions, they could evolve into a civilization-building species following the extinction of humans. Their advanced neural structure, decentralized nervous system, and remarkable problem-solving skills make octopuses uniquely suited for an unpredictable world_”. So octopuses are animals with which we have no common ancestors, at least not over the last 100 millions of years, but with which we share a lot of essential traits, that define us as humans. But apparently not only us ……

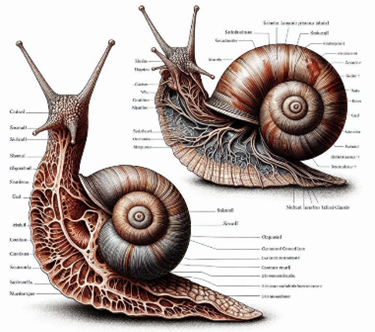

Another interesting phenomenon is ‘atavism’. This is a trait that the ancestors of the ancestors of a species had and the species itself has, but not their link, so not their direct ancestors. Evolutionists state that it is difficult to tell whether this trait has been lost and then re-evolved convergently, or whether a gene has simply been switched off and then re-enabled later. Such a re-emerged trait is called an atavism. The theory is that an unused gene has in time a steadily decreasing probability of retaining potential functionality over time. In mammals and birds there is a reasonable probability of remaining in the genome in a potentially functional state for around 6 million years. A well-known example of atavism is the re-evolution of a coiled shell. The coiling in calyptraeids, a family of mostly uncoiled limpets, have re-evolved at least once within this family. These results concerning the re-evolution of coiling in a gastropod show that the developmental features underlying coiling have not been lost during 20-100 million years of uncoiled evolutionary history. So a complex character re-evolved on the basis of time and not of the basis of external influences.

A third interesting phenomenon is ‘iterative evolution’. This is the process that a species with certain traits becomes extinct, but then after some time a different species evolves into an almost identical creature. I will come back to that phenomenon later on.

One can wonder if ‘convergent evolution’, ‘atavism’ and ‘iterative evolution’ are the result of ‘survival of the fittest’ or that the basics of certain traits are just there to be switched on (and off), possibly by internal or external circumstances, and subsequently used, maybe indeed because it gives the best fit. If you read about the bats and birds, it is clear that their capability of flying is partly the result of different traits but also partly the result of the same traits. So it looks reasonable to expect that their non-flying ancestors already had these last traits in a dormant state in their genes. Not to be used but in store for the descendants to eventually profit from it. If you extrapolate that, you end up with the first living cell and its DNA not only having traits to survive but also having traits in store, or at least their basics, to be possibly used later on during the evolution of life.

About atavism it is even acknowledged that it is about switching on and off of certain genes. The concerning traits stay there for a very long time as dormant traits waiting to be switched on by coincidence or by a trigger. Maybe indeed their basics will never disappear till the end of evolution.

Talking about ‘iterative evolution’, the fact that another species evolves in almost the exact way as an extinct other species, not being an ancestor, is even more an evidence or at least a clear indication that certain traits are available in DNA to be switched on and possibly also off. And not perse in DNA’s that are evolutionary in close proximity. Evolutionists even state that it's highly unlikely that in different species the protein groups would have independently evolved into such similar DNA sequences. The probability of this is much higher if you use the hypothesis of the Excitatus Theory that for instance humans and E. coli are actually related. And where do they meet? Yes indeed, at the start of evolution.

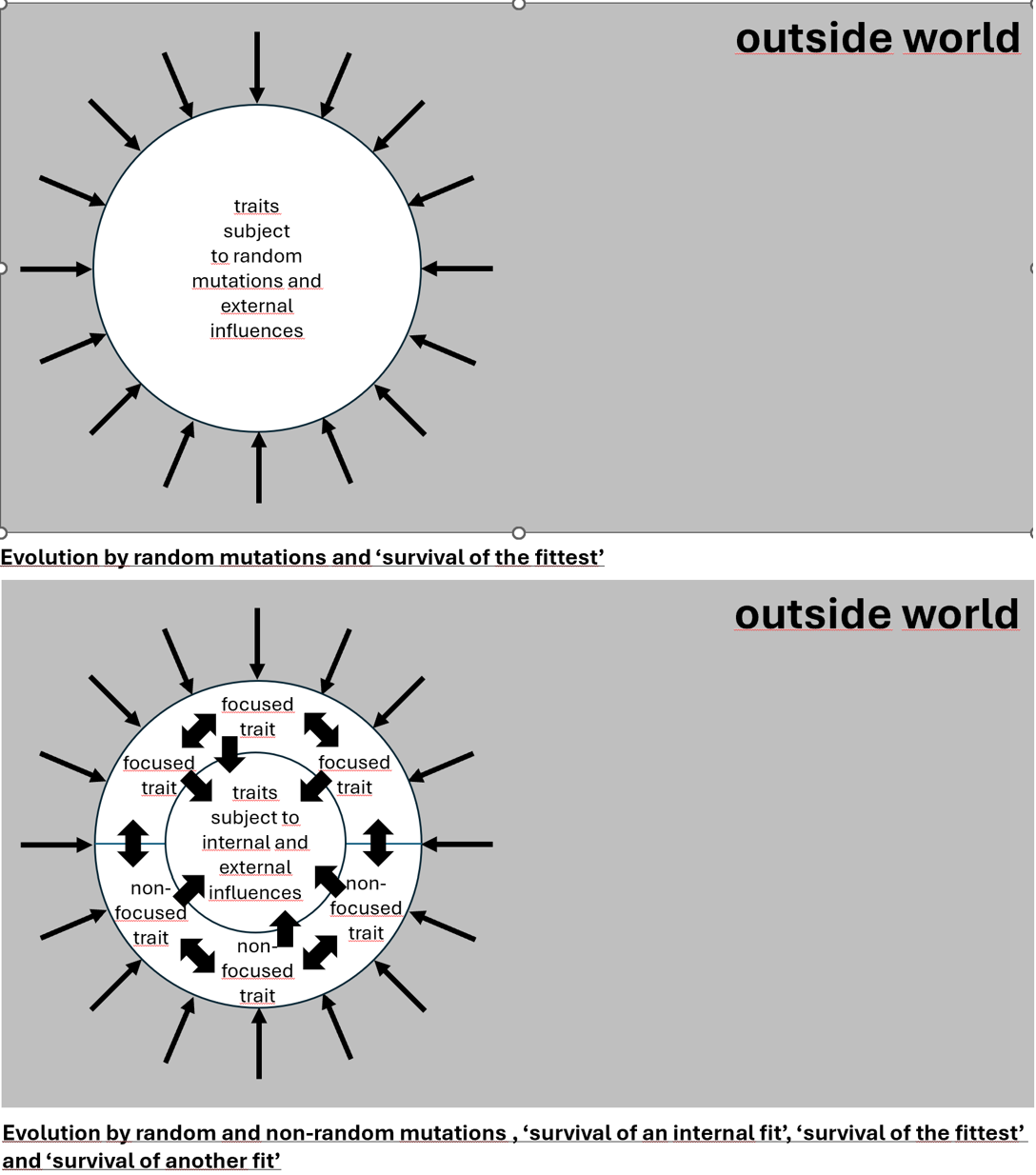

If you combine random evolutionary traits, (potential) focused traits, non-focused traits and obstructive traits than the evolutionary processes resulting in a specific species become way more complex than according to the Evolution Theory. The essence is that according to NI a new trait first has to pass an internal control (‘survival of an internal fit’) before being qualified to pass the external control we know as ‘survival of the fittest’. Or in NI terms: survival of the fittest or of another fit’. The two pictures below give a simplified picture of both evolution theories.

Not only external circumstances and influences determine which mutations can offer a next evolutionary step but also internal circumstances and influences in a more or less complex (depending on the complexity of the concerning species) interaction between traits and so genes. And (again) these last evolutionary processes look to me, though harder to get any insight in, more plausible than an evolutionary process only controlled by coincidences and ‘survival of the fittest’.

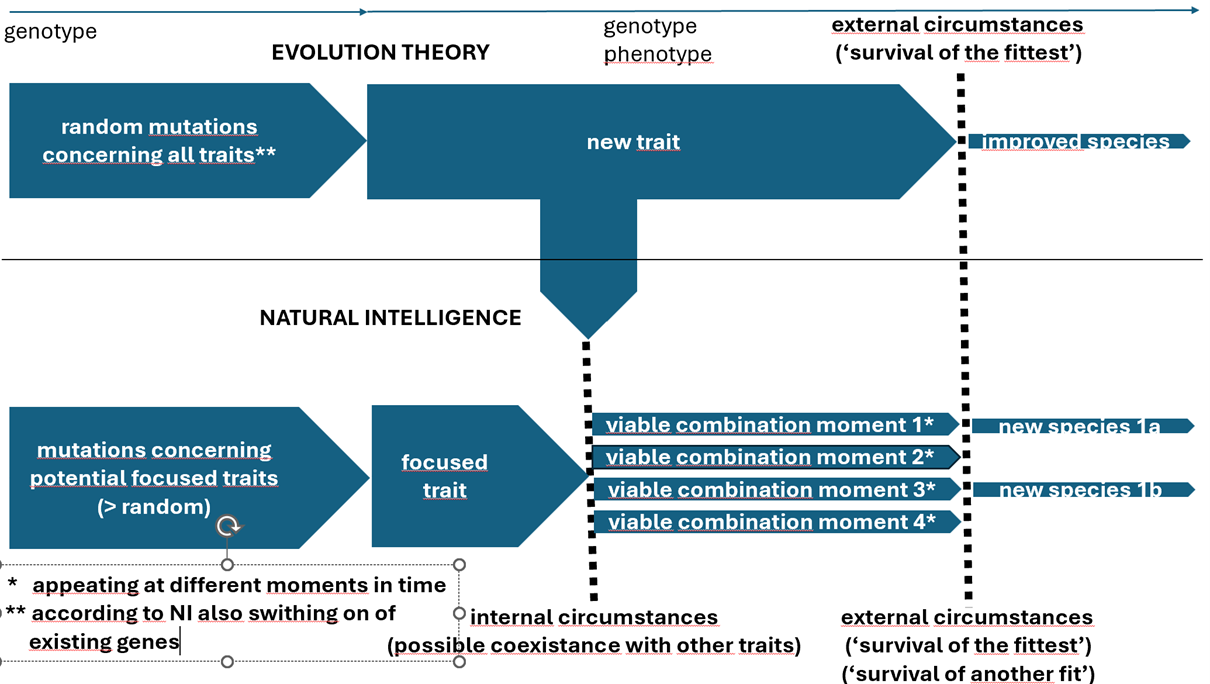

Below a very simplified picture is given of both evolutionary processes leading to a new species (in my opinion according to the ET only to an improved species). A mutation concerning a potential focused trait can lead to a new species right from the start or at any other moment after the start of the concerning susceptibility, depending on the evolution of this (potential) trait and/or of other straits. At a certain moment the evolution of other straits can offer to the concerning (potential) focused trait the possibility to develop the ‘new species to be’ in one direction and at another moment in another direction. Not very different directions, but still leading to variations within a type or family of species.

A well-known term, as already mentioned, in the Evolution Theory is ‘iterative evolution’. This is a natural process of de-extinction and occurs when a species becomes extinct, but then after some time a different species evolves into an almost identical creature. For example, the Aldabra rail was a flightless bird that lived on the island of Aldabra. It had evolved sometime in the past from the flighted white-throated rail, but became extinct about 136,000 years ago due to an unknown event that caused sea levels to rise. About 100,000 years ago, sea levels dropped and the island reappeared, with no fauna. The white-throated rail recolonized the island, but soon evolved into a flightless species physically identical to the extinct species. Looking at the text and the picture above this process of iterative evolution becomes quiet understandable. The potential focused trait of ‘flighlessness’ got its chance a second time.

I am aware that I am making the evolution of life even more complex, opposite to the Evolution Theory just based on two principles. But about the internal processes the ET is a bit of a black box. That is quiet logic because in the time of Darwin there was much less knowledge about genetic processes.

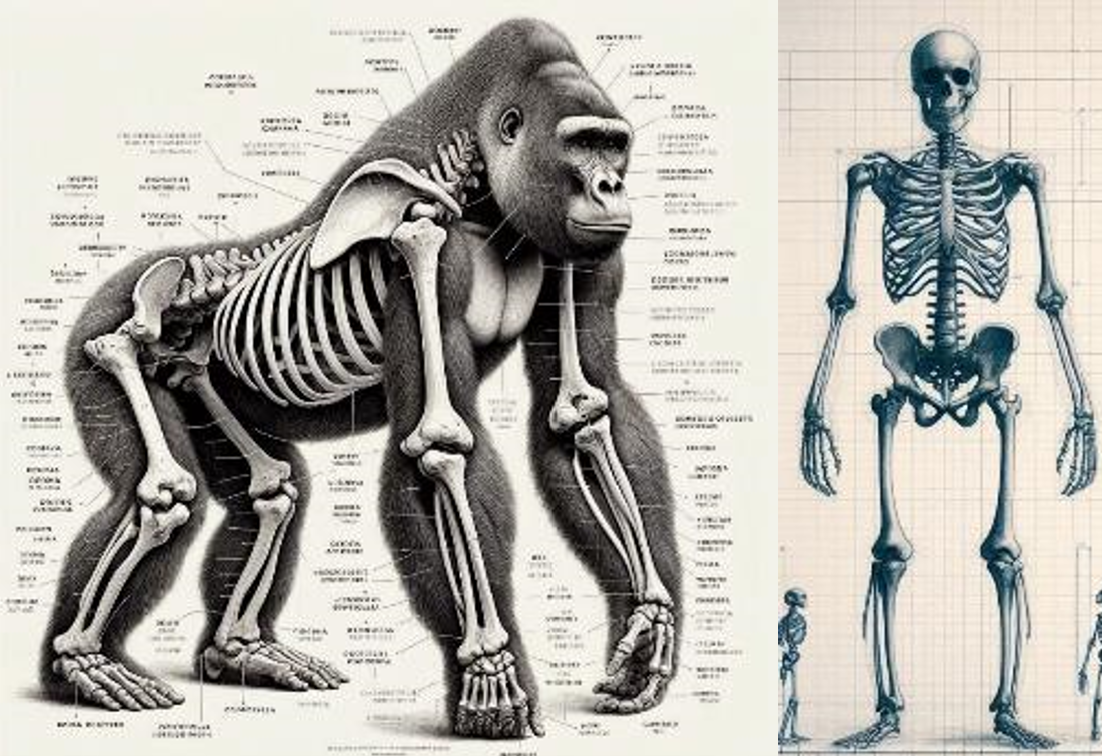

That evolution becomes way more complex, if you incorporate these internal processes. And that the two principles of the Evolution Theory fall short, is easy to understand if only you look of the evolutionary processes that led to men standing and walking upright (or in scientific language going from quadrupedal to bipedal locomotion). A really huge amount of physical changes were needed to go from walking like apes do and our ancestors did, to walking on just two legs. To give an idea here a few of these changes: development of vestibular system, shifting of the point of gravity so we will not fall forward nor backward, change of muscular system, change of bone structure (for instance the pelvis of apes differs completely from that of men), change of nerve system, the hole through which the brain connects to the spinal cord migrated from the back of the skull to the bottom, the spinal column went from essentially horizontal to vertical and the curves that make our spine S-shaped were needed to keep our forward-weighted head and trunk balanced over our pelvis and legs.

Did this all happened just by coincidence? Because walking this way offered the best fit and fortunately all the right mutations happened during this period by coincidence? And all these mutations on their own, and so all intermediate steps, offered again and again the ‘survival of the fittest’? Right! Researchers at Columbia University and the University of Texas have identified 145 locations in the human genome that played a role in the shaping of the human skeleton. And they wrote that their study revealed that the genes driving the skeletal changes were under strong natural selection. In other words: the transition to bipedalism should have offered early humans a clear evolutionary advantage. Many of the genomic regions associated with skeletal development were found to be "accelerated" regions of the human genome, indicating that they rapidly evolved over time compared to the same regions in great apes.

When I read words like ‘_strong natural selection’_, ‘_accelerated regions’_ and ‘_rapidly evolved over time compared to the same regions in great apes’_ than I get three concepts in my mind: ‘revolutionary evolution’, ‘(potential) focused traits’ (switched on by coincidence or by a trigger) and ‘obstructive traits’. To me the happening of all these complex parallel processes just initiated by coincidental mutations is extremely unlikely. And the eventually evolutionary advantages come at the end or at the most halfway the process from quadrupedal to bipedal locomotion.

The only explanation for this clearly directional process and so for the existence of a species walking upright, is that this complex trait, or at least the basics of it, must have been incorporated in DNA long before men started to walk on two legs. Waiting to be switched on and waiting for an internal and external fit. See also the following chapter.