The Origin Of Traits

have already indicated that in my opinion a significant part of the DNA and genes in this DNA, describing the basics of many of the specific traits in which living species evolve and eventually may excel, were already present from the start of life. So in the DNA of the one cell species with which the evolution of life began. Ready to evolve and, in a certain phase or phases, waiting to be switched on. Is that a possibility? Yes I think so. A one cell species contains approximately 2 meters of DNA. And this equals at least 3 billion nucleotides. That is 3 x 109. This nucleotides represent the program of DNA. Seeing this huge number it is not unlikely that the basics of a big percentage of all biological possibilities of nature were already in DNA right from the start. Also the life of every animal, plant and human starts with just one cell. By the way: this makes the statement that only 2% of the human DNA is useful (encodes proteins) and 98% useless, extremely questionable. Parts of this 98% may have no use for humans and other species as we know them today but could have had and/or could have in the future an important function by encoding proteins in ancestors, successors, other animals, plants, at other moments in the evolution of life. By the way: recent research already indicates that at least a part of the mentioned 98% is in reality not useless.

So in my opinion the findings concerning the evolution of feathers can have far reaching implications. The resemblance between the DNA of different species could possibly be not an evidence of an evolutionary process during which one species evolves into another species but of the fact that DNA already from the start of life had many genetic possibilities concerning basic traits incorporated and so because of this start, the DNA of different species have ‘so much’ in common.

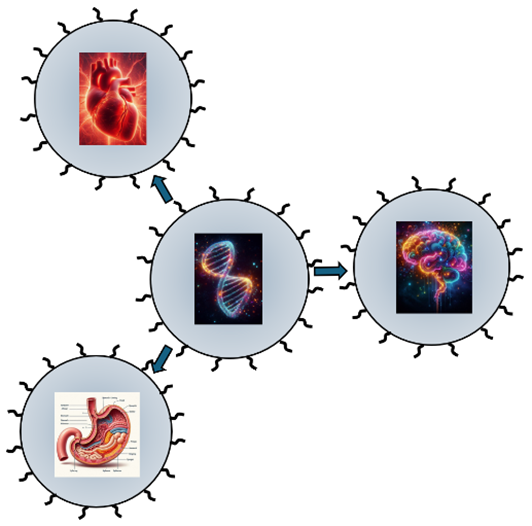

A whole lot of information is already included in one cell and what information is finally used to become a specific capability or trait, is a process of switching on parts of the DNA in this cell. That determines which proteins are going to be produced, which in their turn has a decisive effect on the traits connected with these parts. Of course other traits can play their roll and possibly some more modifications are needed, but it all starts with this switching on of the incorporated basics of the concerning trait. This is nothing special but a process that happens in every newborn. Every living creature starts out as a single cell. This cell splits and these new cells develop into all kind of more specific cells. For instance after fertilization a human cell splits into more than 200 different cell types, like skin cells, liver cells, bone cells, blood cells and so on. Although these cell types look and function differently they contain exactly the same DNA. Chemical processes modify DNA without changing the actual DNA sequence. Genes are turned ‘on’ and ‘off’ at the right time during the development of the cells and which is translated into proteins. Depending on which genes are active at specific times during the development of a cell, the cell develops into a certain cell type. So in this first cell, with which an individual life starts, the basics of all these organs and body parts have to be already present.

So one specific DNA sequence can lead to all kind of different body parts with all kinds of different functions which, on top of that, also work together. Knowing this, one could wonder why it should not be possible and even reasonable to extrapolate that to different species. One can also imagine that genes are turned ‘on’ and ‘off’ at the right time during the evolution of life and so are translated into proteins that, at a certain moment in time, create a ‘new’ trait. So basically the needed sequence is already there, just the right molecular processes to develop this trait, have to happen. Maybe by coincidence or maybe triggered by internal or external influences. So the DNA of the one cell living creature could already have had the potential to develop new traits and so in this way offer the origine of all kind of new species, that are defined by these new traits. The blue print of the evolution of life could already have been there right from the start. To get all the different species, this blue print is probably not enough. In combination with internal genetical processes - like changing sequences, adding autonomous transposons and so on - and external circumstances, it is. But even that in a limited way, as I will show you.

How could that more in detail work: a gene, and with that the basics of a trait, already there waiting to be switched on. Recent research has showed that new traits or ‘switched on genes’ are not the result of a changed DNA sequence. In many species these sequences appear to be very much the same. You could think about a longer DNA, in which these extra length represents this ‘new’ trait. Wrong! For instance the length of the DNA of humans and animals like mouse, dogs and chimpanzees is about the same. And that also applies for the order of genes. When comparing mouse and human genomes, for example, biologists are able to identify a mouse counterpart for at least 99 percent of all human genes. So a gene-similarity among species is the rule. And this has been so during (at least a big part of) the evolution.

So, where are the differences between species come from, where are they settled? This is still a subject of intensive research, so a bit tricky subject. Some researchers claim that the difference is made by the different proteins, the coding genes produce. Other claim that these proteins don’t change much but that is about the change of the molecular processes that influence this protein-making by these genes. What they agree upon is that it is not only about the ingredients but also about the process: where and when the genes are switched on and off.

If we combine these insights, a new trait is the result of a new protein being made by a switched on gene and/or the outcome of a change in the mechanisms that influence this protein-making and/or the result of a different time and place, when and where these processes happen. Then we talk about the terms ‘epigenetic modifications’, ‘transcription factors’, non-coding DNA-sequences and the duplication of genes. It appears that important traits are more the result of the last three influences since changing the proteins, responsible for these traits, is quiet risky because of the possible large impact. So ‘new’ traits are not the product of changes concerning the DNA-sequence and/or the genes themselves. And there are clear restriction concerning changes of produced proteins. Or in other words: the same ‘machine’ (DNA) produces different species mainly due to other settings and other ways of operating.

If we include this in the Theory of ExT, what does this mean? That the DNA-machine, that can produce all kinds of species, is there right from the beginning including the basic capabilities to produce all kinds of traits. Still improvements are needed to make complex traits. So during evolution this machine is improved bit by bit, maybe just by trying (coincidence). There is a manual and there is some staff with a basic training how to operate the machine. But the machine is extremely complex with an awful lot of buttons, clocks, possible processes and so on. So it takes very much time to get familiar with all the possibilities of the machine and to tune all the processes taking place within the machine. In time it more and more becomes clear what will be the outcome depending on when the ‘on’ buttons are pushed and when the ‘off buttons are pushed. And also in what order to do so. A ‘switched on gene’ leading to a ‘new’ trait, and possibly leading to a new species, is nothing more than a discovery (directed or non-directed) by the operators of the machine (the molecular processes) of the capabilities of the machine, to make again and again something new, that is possibly marketable (new fit or ‘survival of the fittest’).

Inside DNA the production of a new trait is like operators of a machine discovering an until recently unknown capacity of this machine - and how to handle that - which is capable to manufacture a new (possibly) marketable product. The input of materials does not change significantly; sometimes the amount per material may have to change a bit. The essence of this is that basically it indeed is and always has been (more or less) the same machine (right from the start).

Above I made an extrapolation comparing the development of an embryo with the development of a new species. At recent research confirms that both – splitting of cells and switching on genes and other molecular processes – have in common that it all starts with one DNA-sequence. During the development of an embryo the DNA does not change at all. And during the evolution of life these changes are often limited to even extremely limited. In my opinion especially this last finding is (almost) an evidence that my “Excitatus Theory’ (I will present in this chapter) is the right evolutionary theory or at least a theory that deserves attention and should be considered as a theory not less relevant than the Evolution Theory. I am aware that this sounds a bit presumptuous, but ok.

Further on, I will discuss the origin of life and that it is hard to image something (life) originating from ‘nothing’ (combination of dead materials). But also during specification according to the Evolution Theory a more or less similar process is taking place over and over again. For instance, did the first species with the capability to sense noise develop the necessary DNA-code to do so out of nothing? How? How can a mutation or couple of mutations by coincidence lead to such a complete new feature and trait? Like screwing a car together and, because of a mistake (mutation), suddenly a refrigerator appears.

So I think that of all primary traits developed by all species during the evolution of life the basics, offering to mutations the chance to develop these traits, must have been there from the start of life. This presence right from the start, and the switching on and off of the concerning parts of DNA, is the essence of the Excitatus Theory. To explain the difference between a primary and a secondary trait you should think of hair versus the quills of a porcupine or teeth versus tusks of an elephant.

The basic traits evolved during the first billions of years because every ‘simple’ and every (more) complex living creature needed them and because in this period these basic traits were good enough to make a decisive difference. And also because more complex traits will take more time to find a fit (‘survival of an internal fit’): it takes more time to find a viable and favourable combination with other traits.

I will give so more some support to this theory, it is good to know that the shaping of bodies of animals is controlled by a rather small percentage of genes (less than 10%), and that these regulatory genes are ancient, shared by all animals. For instance the giraffe does not have a gene for a long neck, any more than the elephant has a gene for a big body. Important in this respect is the so called ‘Toolkit genes’. This implicates a couple of genes that together define the body plan and the number, identity and pattern of body parts. They are qualified as highly conserved. Differences in deployment of toolkit genes determine their outcome. The protein products of the regulatory toolkit are reused, being applied unchanged in many independent developmental processes, giving pattern to many dissimilar body structures. It concerns complex genes and complex working genes and this complexity enables these genes in the development of the embryo to be switched on and off at exactly the right times and in exactly the right places. Which has a determining effect on the result.

If the basics of all essential traits were already present in DNA right from the start and if a new trait can only evolve out of these basics and not out of zero, than this also implicates that traits, of which no basics are present in DNA, will never evolve during the evolution of life. So some traits should be excluded. Which one you and I wonder. I have been thinking about that. So what about flies flying like helicopters? Or fishes with some kind of organ looking like a propeller. Indeed these require a kind of joint that can turn 360 degrees. Maybe physically too difficult to incorporate in the phenotype? Mammals with 4 legs and 2 arms? Reptiles with incorporated air bubbles to stay longer under water? Animals that produce poisoned sweat if attacked?

Besides these possible useful traits you could expect, if traits indeed develop out of zero, at least the first beginnings of some useless traits. Difficult to imagine but maybe something like an organ to produce air bubbles, or an organ to cool air or make summersaults.

According to the Evolution Theory it was expected that the diversity of body plans and morphology in organisms would be reflected in diversity at the level of the sequences of genes. But research contradicts this. As John Gerhart and Marc Kirschner (two acknowledges biologists) have noted, there is an apparent paradox: "_where we most expect to find variation, we find conservation, a lack of change_". Small changes in toolbox genes cause significant changes in body structures. A small fraction of the genes in an organism's genome control the organism's development. So this fact, that a small fraction of genes determines the development of the body of a species, that these genes are present in all animals and that this basic genes are capable to produce an huge variation of body shapes, from snakes to elephants, is in my opinion not an evidence of some common ancestor but of one common ancestor: the one cell species with which it all began (often named LUCA) already carried this toolbox genes.

This is the 4th key point of NI and ExT (the genes, that can produce the proteins needed for all basic traits, were already in their basics present in DNA from the start of life). And I have also arrived at the 5th key point and that is ‘tuning’.

That concerns the processes connected with the ‘survival of an internal fit’ and the ‘survival of the fittest”. I already presented non-focused traits, potential focused traits, focused traits and obstructive traits and the way they interact. Some of them are showing themselves in the species as we see and experience them and so, in connection with that, in fossils. I have showed how the trait ‘body weight’ hindered the potential focused trait of flying to become a focused trait. So no birds yet. In the beginning there was just no ‘survival of an interna fit’. And probably the first birds, that could only fly a bit, were still so heavy that they could not get high enough into the air to escape all animals hunting them. So not yet a ‘survival of an external fit’ or in the terms of the Evolution Theory no ‘survival of the fittest’. When the body weight dropped even more also this second hurdle was overcome and birds, as we know them, really appeared.

I have showed this also schematically. These kinds of processes - the tunning by time between traits that impact each other - happen in the ancestors of a new species, before one or more of these ancestors find the right tuning and so become(s) in person this ancestor. Researchers found, as already mentioned, that the codes for feathers were already there 100 million years before the first bird appeared. And according to ExT probably even right from the start. So this is a clear indication of how long this process of tuning can take before reaching a positive result.

I already described the function of toolbox genes and the big surprise that the shape of the body and body parts of every animal is controlled by the same genes. The complexity of this part of DNA is way less than was expected. The complexity lies in the way these genes are being activated, where and when. That is an extremely sensitive process that determines the outcome of these genes. That is where the tuning and also fine-tuning are coming in.

So during evolution we see two phenomena leading to more and more complex species. A moderate if not limited increase of the complexity of the genome and the development of a very complex guidance of the activities of the genes that determine the development of a species and also of every embryo of this species.

What does this tell us? That the evolution of life was and is not only about numerous mutations resulting in a more advanced and complex genome and so species, but also - and maybe even more - about tuning and fine-tuning the processes in this genome in order to reach an internal and external fit between the traits that are the result of this genome and these processes. If you read about the complexity of these processes, on a molecular level and of a physical level (traits influencing and hindering each other), it is easy to see that this is a very time consuming process. Controlled by coincidental mutations and changes and, where applicable, sped up by the effect of (potential) focused traits.

So one important reason, that dinosaurs preceded the mammals, could be that it was easier and so faster to reach a fit within dinosaurs than within mammals. It I easier to tune a few (focused) traits than it is to tune a lot of these traits.

You could compare the evolution of life with an orchestra learning to play a symphony. To reach a level, that an audience will enjoy the concert, and so is willing to pay for it, a lot of conditions have to be fulfilled. First you need the right instruments depending on the orchestration. Violins will always be needed, like cello’s. Other less standard instruments can be added. But the basics of an orchestra is always the same. Then we need musicians to play the instruments. Further we need a composition, a conductor and the time and space to rehearse. The problem is that there is only a very basic composition for only the basic instruments. Not much more than some first notes, the key and the meter are known. So only a few players know at what moment to play which notes. All the other players therefor stay asleep. Another problem is that the musicians are just enthusiastic beginners. The first song only lasts 5 minutes. But everybody, also the not yet demanding audience, is happy with this first rudimentary song and performance. As soon as the harmony is reached, it is put on paper. But after a while, hearing this same song over and over again, the crowd is getting a bit bored and is not willing to pay anymore only for this simple music and mediocre musicians. They want to hear more. So the members of the orchestra don’t earn enough money anymore to survive. By coincidence or because of some actions of the conductor, some sleeping players awake. Maybe because they are also getting hungry. So being awake they try to play along with the melody. In the beginning it really sounds horrible. Luckily some instruments can play some of the notes already put on paper. Nevertheless people start booing. The new players make an extra effort to pick up the melody, the conductor gives instructions, the players rehearse many times and so are getting better and better. Maybe partly also by coincidence a new musician hits a right note and tries to remember it. So slowly but steadily the music starts to sound better and finally a harmony is reached. Again this is put on paper. The audience hears something new and is willing to pay again. The playing members of the orchestra become professionals, so the music sound better and more complex and again everybody happy. But then is starts all over again: a percentage, not all, of the audience is getting bored. So again other musicians are asked to join in. And they do this again, which gives - after mismatches, trying all kind of variations, rehearsing and fine-tuning - a positive outcome. The song is becoming ever more complex, more instruments involved, more variations and also longer. Some people stay with the more simple versions, some go to the more complex versions and also new audiences are willing to listen to the more complex versions of the tune and pay for it. The audience is happy again, but after a while some of them don’t want to hear all these simple and more complex variations of the same tune over and over again. And also there is still a large group of people that is not coming to the concert hall at all. So there is room for another melody, another symphony. And so the whole process starts all over again in order to be able to play two melodies. The players are better prepared and are more experienced but the audience is getting more demanding. They want to hear something else. Not the same orchestration and there are still instruments untouched. The experienced players have to play more complex cords, music in another key and also new instruments are coming in. But the composition is again incomplete. So on a bit higher level the whole process of failing, trying, rehearsing, finding the right harmony, and so on, starts all over again. After a lot of time has passed, because of the higher complexity of the composition, the playing of a second symphony is ready. Everybody happy and because of the better musical quality the people coming to the concert are willing to pay more. Many years later the orchestra is even able to play many symphonies in different keys and meters, in a more simple form and in more complex forms. Not only classical but also modern and even rock. Every performance has its own audience. Some people visit two or even a couple of concerts. There are also people who hate some of the music played. After a while some music gets outdated, people want to hear new things, or existing music but played in another way. This results in a combination of evergreens, new melodies, enhanced melodies and so on. ©2024 oke

I hope you can follow the parallels between this story and the evolution of life and that you can agree. But nevertheless, to make sure, I will give some explanations (I am aware that I lack the knowledge to describe all processes going on and all the players active in a cell in detail and that the analogy, I present, has its limitations):

| Orchestra | DNA |

| Music | llfe |

| Instruments | basics of traits |

| Key instruments | basics of traits every living creature needs |

| Players | transcription factors, key regulators etc. |

| Sound | RNA, chemical processes, proteins and so on |

| Conductor | RNA, chemical processes and so on |

| Basic composition | one family of species |

| Failing, trying, rehearsing, | |

| trying variations | mutations, developing traits and tuning and fine tuning between traits |

| Harmony | internal fit |

| Putting on paper | codes to program a certain species and its traits |

| Instruments can use notes | |

| put on paper for other | |

| instruments | phenotypic integration |

| Symphony | phenotype of a species |

| Audience | biosphere |

| Applause, paying visitors | external fit |

| Booing, less audience, | |

| hunger | external trigger |

| Simple version | less complex species within one family |

| More complex version | more complex species within one family |

| Change of performance | new species within one family |

| New key, rhythm, type of | |

| music | new (potential) focused trait |

| New melody/symphony | new family of species (caused by revolutionary evolution) |

| Outdated music | ancestors |

You could argue that with the theory, that the basics of all primary traits were there already from the beginning, I make it harder to explain the origin of life without some creator. But is it not harder to explain that without a creator during evolution thousands of times new decisive traits appeared more or less out of nothing? That for some reason a new protein appeared that for some reason opened the genetic way to a favourable new trait and not to something useless. The chances of something useless to appear out of a random process instead of something useful, is trillions if not infinite times bigger. So no, I don’t think I make this harder. The genes, leading to the production of specific and useful proteins, and the opportunity that mutations result in other proteins, which in their turn offer the possibility to develop new fruitful traits, must have been there right from the start. Otherwise the origin of every new trait is an as big enigma as the origin of life itself.

All evolutionists agree that the first living cell already must have had a number of essential programmed traits to survive and to produce ‘offspring’. I am speaking about traits like self-replication, photosynthesis, protection from the outside environment, confinement of biochemical activity, enzyme production, cellular compartmentalization, metabolism, catalytic molecules, transport mechanism, basic homeostasis, absorption of nutrients, excretion of waste and so on. So the fact that all these features already must have been there right from the start, implicates that the step to also incorporate the basics of traits, essential to more complex species to come, is not that unlikely and farfetched.

By the way: to have an open mind one should not (in advance) include a kind of creation or creator but on the other hand you should not be afraid to go a way that makes it harder to exclude that, if this way looks to offer a (more) realistic view on evolution. An open mind means that you have to be prepared to go all plausible ways.

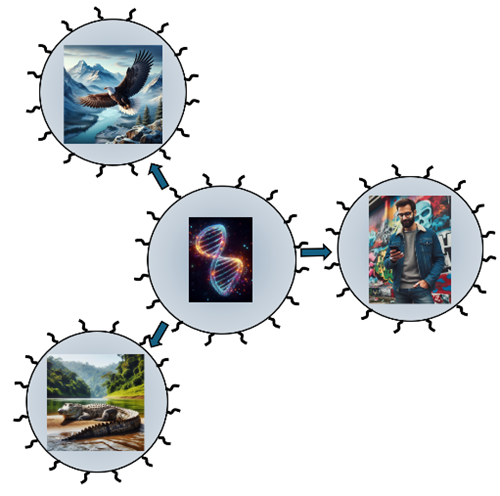

If this starting point is correct (the basics of primary traits were there already from the beginning), than why did not every living species ‘choose’ to go for the human direction, so for intelligence as the focused trait? The possible explanation is ‘coincidence’, if we are talking about passive susceptibility, or not the right trigger at the right moment under the right circumstances, if we go for active susceptibility. And also the interactions with other traits at any moment (internal fit) during evolution and with external circumstances (external fit) could have played a decisive role there.

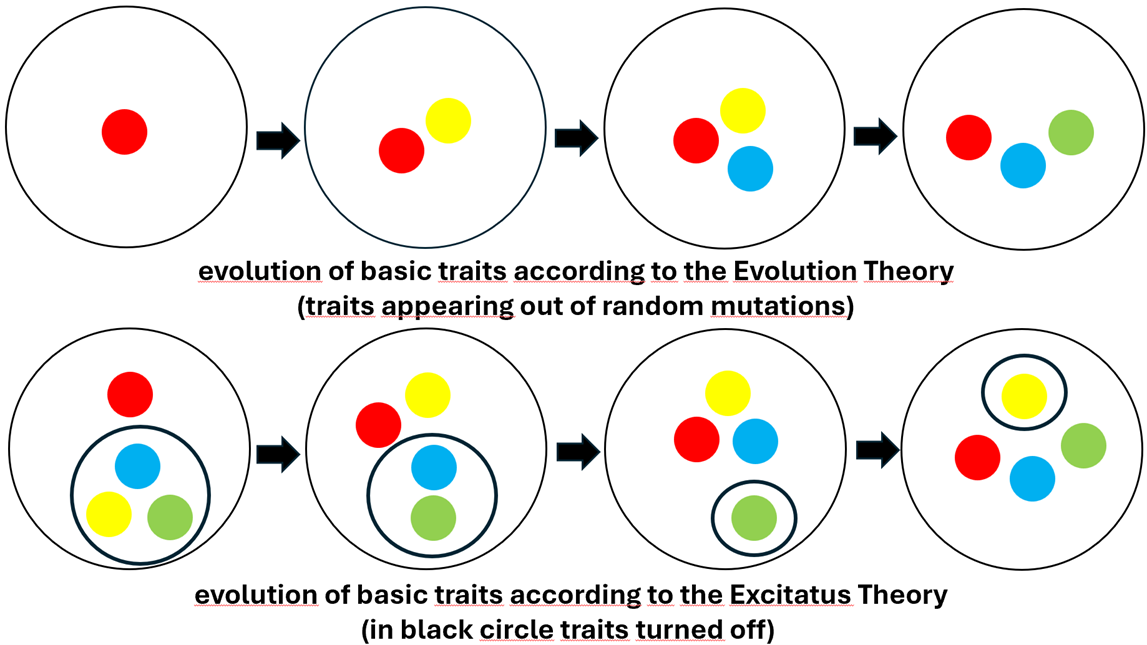

Below an extremely simplified picture is given of the evolution of life according to ET and one according to ExT. During the first evolutionary process a new trait appears by a random mutations (instead of or next to an existing trait). By luck this new trait offers a better fit. During the second process, beside the existing trait, there are genes ‘waiting’ to be activated. This activation could come or not, dependant on their evolution. Also the evolution of other traits are relevant in this situation. If activated and giving an internal fit this new trait could also externally offer a better or different fit. It is also possible that an existent trait goes into a dormant state or is even switched off.

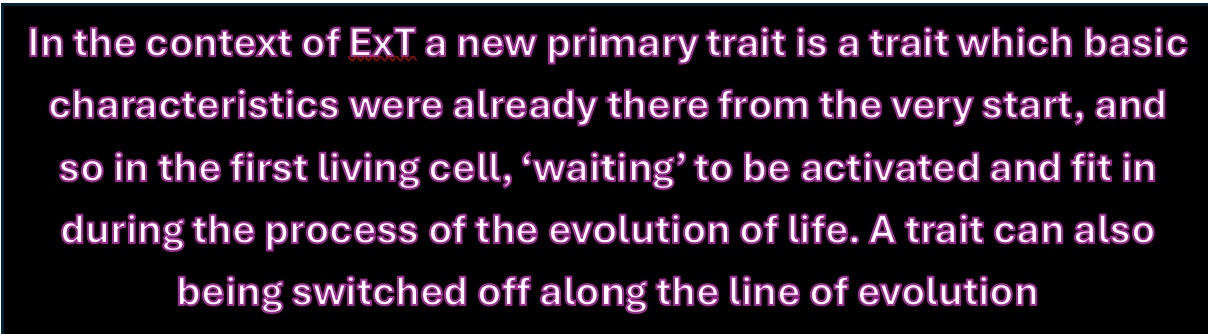

A new primary trait according to ExT is a trait, which basic characteristics were already there from the very start, and so in the DNA of the first living cell, ‘waiting’ to be activated during the process of the evolution of life and possible even to become at a certain moment a focused trait. This latest switch can only happen by an enhanced susceptibility. A trait can also being switched off along the line of evolution.

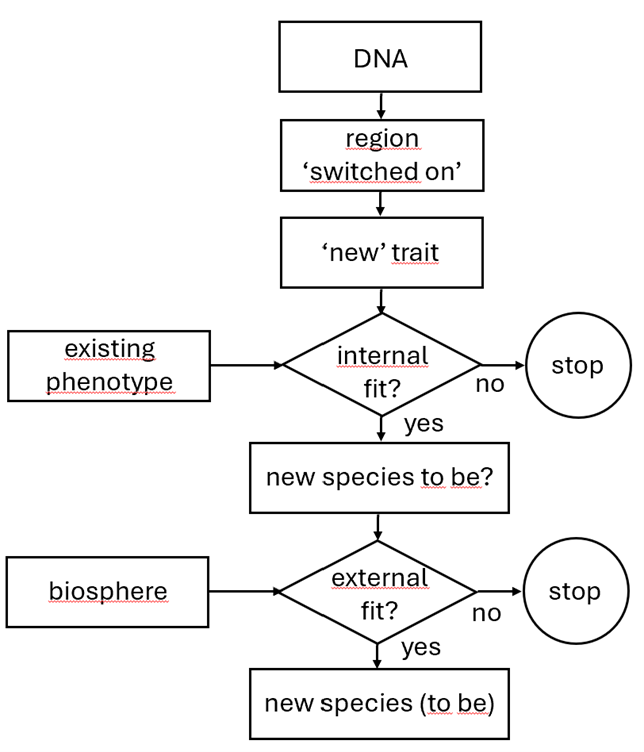

Below you find a flowchart of the process that can lead to the origine of a new trait. Not based on random mutations that produce a new trait from scratch, that finds its way to a species if this trait implicates a ‘survival of the fittest (ET). But based on switching on a region in the DNA (meaning for instance the production of a new protein or a change of the molecular processes that influence this protein-making) that produces a ‘new’ trait. Every time this mutation indeed happens, the process according to the flowchart will be followed. If the mutation happens, the result (the ‘new’ trait) will be checked within the concerning species: does the new combination offer a viable fit? If not, the concerning species with the mutation will die and so no new species will develop. If there is an internal fit, one or a couple of species will appear with this change. Does this change not represent a ‘survival of the fittest’ or another viable fit, this species or these species with the ‘new’ trait will die and so no new species will develop. But if one of the two last fits is there, it could be the starting point of a new species or an improved existing species.

Beside the fact that it appears that the basics of some traits were there, genetically speaking, already for a very long time before a living species made use of them to survive and to become successful, there is something else that until now researchers were not able to explain. The more complex a living creature the more protein-coding genes it has. A worm for instance has 19.000 genes while a human has 20.000. So not really much more (as already indicated before). Also the genome sizes can increase with the complexity of the species (humans three times the length of worms).

The number of traits worms have is estimate at between 1000 and 3000 and the number of (more complex) traits humans have is estimated at between 10.000 and 20.000). So humans have 5% more genes and the genome is three times longer. But the number of (partly more complex) traits could be about 12 times more (average between 3.3 and 20 times). This can only be explained if in reality the number of traits in worms is much bigger than the mentioned number, but most of them are just switched off.

Well know is the The Chickenosaurus Project lead by Jack Horner and supported by may others. The idea of this project is using genetic material of chickens to reverse the evolutionary process and so to create a creature resembling their dinosaur ancestors out of this DNA. This is done by manipulating the dormant (or atavistic) genes that were active in their dinosaur ancestors and surpress other genes. By manipulating these genes, scientists might reactivate traits like snout in stead of beak, forelimbs instead of wings and dinosaur-like tail. Some progress have been made like altering chicken embryos to develop snout-like structures instead of beaks. The logic behind this project and the results so far seem to support The Excitation Theory (and not the Evolution Theory), that evolution is indeed a process of switching on and off of genes and molecular processes.

The length of the DNA does sometimes corresponds with the complexity of the living creature but that is not a law. The animal with the largest DNA is the marbled lungfish which has 130 billion base pairs in one DNA string, while humans have only 3.2 billion base pairs. So that is more than 40 times less. So called autonomous (non-protein producing) transposons are responsible for this. These are DNA sequences that "replicate" and then change their position in the genome, which in turn causes the genome to grow. So a longer and more complex DNA does not implicate new genes (and so traits) but more of the same.

These fishes have way more of these transposons than human beings and because they don’t produce proteins these transposons have no direct effect on the traits of a species. In the past, as already mentioned, these parts of DNA were labelled as waste. These autonomous transposons, sometimes qualified as ‘jumping genes’, can be important drivers of evolution, as they sometimes cause evolutionary innovations by altering gene functions. Researchers are beginning to appreciate how this noncoding (no proteins producing) DNA can be a genetic resource for cells and a nursery where new genes can evolve. Because dynamic noncoding sequences can produce so many genomic changes, the sequences can be both the engine for the evolution of new genes and the raw material for it.

Let us take a bit closer look at this marbled lungfish. Despite being aquatic, adult marbled lungfish can live in riverbeds and other areas that have no rain during periods of the year, due to their ability to estivate or burrow in the ground to form an air bubble and breathe out of a hole in the cocoon thus formed.

So this is quiet some animal: evolutionary going from water to land, (further) developing their lungs and (some sorts) limb-like fins to be able to move on land and after that going back into the water again. The limb-like features going more or less back to fins. That needs an awful lot of in time changing (focused) traits during all these processes to make this very complex evolution possible. So maybe the length of the DNA of a species is not so much related to the complexity of this species but to the complexity of its evolution. If you consider the mentioned possible function of the non-coding DNA concerning the altering and innovation of gene functions one could suspect a mutual relationship: more (r)evolution means more non-coding DNA and more non-coding DNA means more (r)evolution. In fact researchers found evidence that the transposons responsible for the growing of the DNA of the marbled lungfish are still active. So again an indication that evolution is not only the result of random mutations. Because mankind has had more evolutionary developments than worm, the already mentioned different length of the DNA between both species, can also explained: not because more new straits had to develop in humans but more evolutionary steps were made. And also the fact that all essential evolutionary changes has resulted in about 23000 protein coding genes in a marbled lungfish, so hardly any more than humans, is an indication that extra, new or changing traits are not coming out of nothing and so lead to an all the time increasing number of genes, the more evolutionary steps have been made. Indeed most of the time it is mainly about switching on and off of existing genes.