Why Are Fossils Of Transition Forms Rare?

Switching on and off of genes offers the opportunity to explain evolutionary processes the Evolution Theory can’t. At least in my opinion. I already mentioned the transition from quadrupedalism to bipedalism as a result of many mutations, where each individual mutation on its own would have offered zero better fit, if not a worse fit. Meaning that this process would have stopped as soon as it began if ‘survival of the fittest’ was the only engine of evolution.

Another example is the transition from ‘laying eggs’ to ‘giving birth’’ (viviparity). This transition occurred independently in several lineages of animals. Researchers found that the switch from egg laying to live-bearing is caused by around 50 genetic changes that are scattered around the snail genome. Yes, this research was done on snails, so it looks reasonable to expect that in respect to mammals the number of genetic changes will at least be as large. Overall, the researchers write, the results suggest that live-bearing evolved gradually through the accumulation of many mutations that arose over a period of 100,000 years. But the precise benefits of live-bearing in these snails remain a mystery: by solving one problem, live-bearing would have certainly created others. “_The extra investment in offspring would have almost certainly placed new demands on the snails’ anatomy, physiology, and immune system. It’s likely that many of the genomic regions we identified are involved in responding to these types of challenges_.”

So a mystery why this process started and why it continued. What where the benefits of the end result and of every of the 50 individual mutations in between? The ‘survival of the fittest’ has no answer. And NI and ExT? Yes, I think so. Or at least a possible explanation.

First: a change of one or more (potential) focused traits could have started the process. That genetic change does not need a reward like ‘survival of the fittest’. This (potential) change is more or less pushed upon the concerning individuals. And as long as it is not life threatening or a major setback, no reason to make a fuss about it if the potential focused trait becomes a focused trait. So it all began with switching on, by internal or external circumstances, of a relevant gene concerning viviparity resulting in the focused trait of ‘giving birth’. Because mutations, concerning this type of traits, happen more frequently than to be expected on the basis of a random process, an individual or a group of a species was/were born with this focused trait, with some frequence. It is written that ‘giving birth’ evolved independently in several lineages of animals. So it concerns a trait which basics were already present in DNA; maybe even right from the start. So this fact, in combination with ‘giving birth’ being a focused trait, makes the chance of a change from ‘laying eggs’ to ‘giving birth’ many times bigger than if this all has to happen on the basis of traits appearing out of nothing and also being the result of just coincidental mutations. If this trait didn’t kill this individual/group, the trait could be there in vain because the other 49 straits, needed to make it work, were not (yet) present. So it/they could carry for instance the veins needed for giving birth, but with no use (and no harm).

A fundamental evolutionary change or innovation is on the basis of the existence of potential focused traits many times more likely to happen (and so logical) than on the basis of the evolvement of the needed new traits out of random mutations with no prior genetical basics concerning these traits.

It is imaginable, because the concerning mutations are happening again and again during evolution in more than one lineage, that by coincidence some of the species that got the focused trait of ‘giving birth’, also had by coincidence some of the other 49 traits like the mentioned veins. But all? Not very likely. So what could make it more likely that the focused trait of ‘giving birth’, when it appeared in an individual or in a group, was supported by the presence of all the other needed traits to make it together work? There are a few possibilities:

- The mutation in the DNA-code, that led to the switching on of the focused trait ‘giving birth’ caused a ‘snowball effect,’ so initiating more mutations concerning the other 49 relevant traits;

- The other traits where already there, but in a dormant state, (more or less) awakened by the focused trait;

- In the development of an embryo the ‘players’ there, which are responsible for switching off and on of genes at the right moment and location to let the embryo develop in the right direction, changed their behaviour when they ‘discovered’ the new trait of giving birth;

- A combination of 2 or 3 of these possibilities.

I will focus on the possibilities 1. and 2. or a combination of both, but I certainly don’t want to exclude possibility 3. In evolutionary developmental biology that process is called heterochrony and concerns any genetically controlled difference in the timing, rate, or duration of a developmental process in an organism compared to its ancestors or other organisms. This difference leads to changes in the size, shape, characteristics and even presence of certain organs and features. For instance in a chimpanzee the foetus brain and head growth starts at about the same developmental stage as that of humans and grow at a similar rate. But in chimpanzees growth stops soon after birth, whereas in humans brain and head growth continues several years after birth. Humans have, compared with chimpanzees, some 30 different body developments that are being delayed or slowed down, resulting in features such as a large head, a flat face, and relatively short arms. This implicates also a prolonged childhood and retarded maturity.

Which one of the above named evolutionary processes is the right on, if any, I don’t know. But a process like this or similar to this, must have happened, because a process of 50 independently occurring mutations, all by coincidence, leading again all just by coincidence to ‘survival of the fittest’ and the complex trait of ‘giving birth’, is not only unlikely but completely impossible (in my opinion).

You may wonder if ‘giving birth’ as an evolutionary ‘package deal’ is not also something unlikely. But this is not something genetically unprecedented. Because life from the very start was already some kind of ‘package deal’ considering all the traits the first living cell needed to stay alive and to reproduce. By the way: I have no clue if this package ‘of giving birth’ was coded in DNA right from the start or if it (partly) gradually evolved in that way, ruled by certain processes or even by coincidences. But the basic theory is that there is one focused trait which pushes ‘giving birth’, or a significant part of this evolutionary path, upon species and that this focused trait takes other traits along his path by waking them up (by making their already present basics to become active or by activating, so far useless, traits) or by causing a specific, coherent snowball effect of mutations.

NI makes it easier to accept something like a ‘package deal’ than the Evolution Theory does. Meaning, traits that somehow more or less purposely work together to reach a certain effect, like ‘life’, like ‘giving birth’ and like ‘walking upright’ (in genetics complex traits are traits that are phenotypes that are controlled by two or more genes; here with complex traits I mean an essential trait that can only work on the basis of a combination of more than a few, coordinated sub traits. So there is an overlap but it is not the same).

How could possibility1. work?

I introduced the term ‘package deal’ as a cooperation between separate traits to make together a complex trait work. In the science of genetics there is already a term for this and that is Phenotypic integration. Phenotypic integration provides an explanation as to how traits are integrated, organized, and made into a functional whole. Indeed an internal fit after reaching harmony. Integration is also associated with functional modules. According to Phenotypic integration it is important for the concerning traits do evolve together (by the way: to my opinion mutations that influence each other is not something random).

If all features of an organism are completely integrated, the parts will be prevented from evolving independent adaptations (‘harmony’ is out of reach). Therefor these ‘packages’ are supposed to influence the traits within the same package but not the traits in other packages. This is called Modularity. At a genetic level, integration can be caused by for instance pleiotropy or Genetic linkage.

Pleiotropy occurs when one gene influences two or more seemingly unrelated phenotypic traits. Mutation in a pleiotropic gene may have an effect on several traits simultaneously. The underlying mechanism is genes that code for a product that is either used by various cells or has a cascade-like signalling function that affects various targets (so a ‘snow-ball effect’). Pleiotropy can have an effect on the evolutionary rate of genes and allele frequencies. Traditionally, models of pleiotropy have predicted that evolutionary rate of genes is related negatively with pleiotropy – as the number of traits of an organism increases, the evolutionary rates of genes in the organism's population decrease. This relationship has not been clearly found in empirical studies for a long time. However, a study based on human disease genes revealed the evidence of lower evolutionary rate in genes with higher pleiotropy.

I think this is quiet easy to explain. If there is a (potential) focused trait pushing the evolution, this can compensate the expected decrease (because it takes more efforts to reach ‘harmony’) and where this is not so, this decrease will be there, as expected (not compensated by more than random mutations).

Genetic linkage involves multiple genes being inherited together because they are close to each other on the same chromosome. Alleles at different loci can be inherited together if they are tightly linked. Transposition allows the loci at different locations on the chromosome to move so that they can become close to each other and be inherited together.

An important example of phenotypic integration evolving over time is the relationship between the number of bones in the brain and the size of the brain. Over the last 150 million years the number of bones in the brain has decreased while the size of the brain in mammals has grown. Integration between the brain and the skull has evolved over this time period to reduce the number of bones in the skull, while increasing the size of the brain.

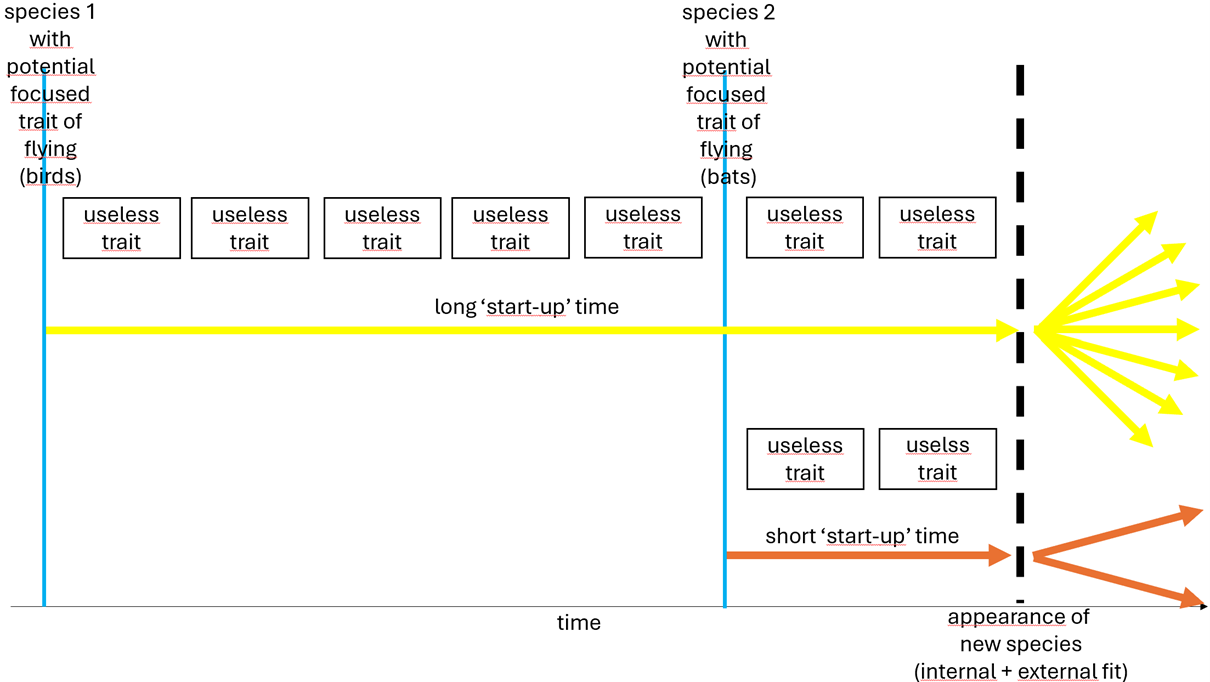

New Cornell University researchers (Andrew Orkney and Brandon Hedrick) have found that, unlike birds, the evolution of bats' wings and legs is tightly coupled, which may have prevented them from filling as many ecological niches as birds. It was expected that the evolution of bats was similar to that of birds, and that their wings and legs evolved independently of one another. But the opposite was found. The researchers observed in both bats and birds that the shapes of the bones within a species' wing or within a species' leg are correlated. Meaning that within a limb, bones evolve together. However, when looking at the legs and wings, the results were completely different: Bird species showed little to no correlation, whereas bats show strong correlation. This means that, contrary to birds, bats' forelimbs and hindlimbs did not evolve independently. So this suggests a coupled evolution of wing and leg. This coupled evolution had two positive effects on the speed of evolution. Less favourable mutations were needed and ‘harmony’ was easier to reach.

How could possibility 2. work?

One can imagine that a trait can be present it the genotype and even the phenotype without any function, as long as it does not have any (decisive) negative effects. We as humans have at least 100 of these so called vestigial anomalies. The most renowned are the appendix, wisdom teeth, coccyx and male nipples. So, for instance, if because of a mutation some men are going to develop mammary glands, the last attributes will prove to be handy and so don’t have to develop independently (by coincidence). The definition of Vestigially is the retention, during the process of evolution, of genetically determined structures or attributes that have lost some or all of the ancestral function in a given species. But in accordance with NI and ExT these structures or attributes are not remnants of an ancestral function but Phenotypic conditions that will make possible future evolutions of more complex traits, easier and so more likely.

So the above mentioned processes of coupled mutations and already in a dormant state present traits makes a fundamental new trait, that needs 50 mutations to happen, significantly less unlikely. A (potential) focused trait and the basics of new traits already being there, also make such a evolutionary process way more easy to accept. But is this enough for time to do its work? I doubt it. So what other possibilities are there to switch for ‘still not very likely’ to ‘a real possibility’?

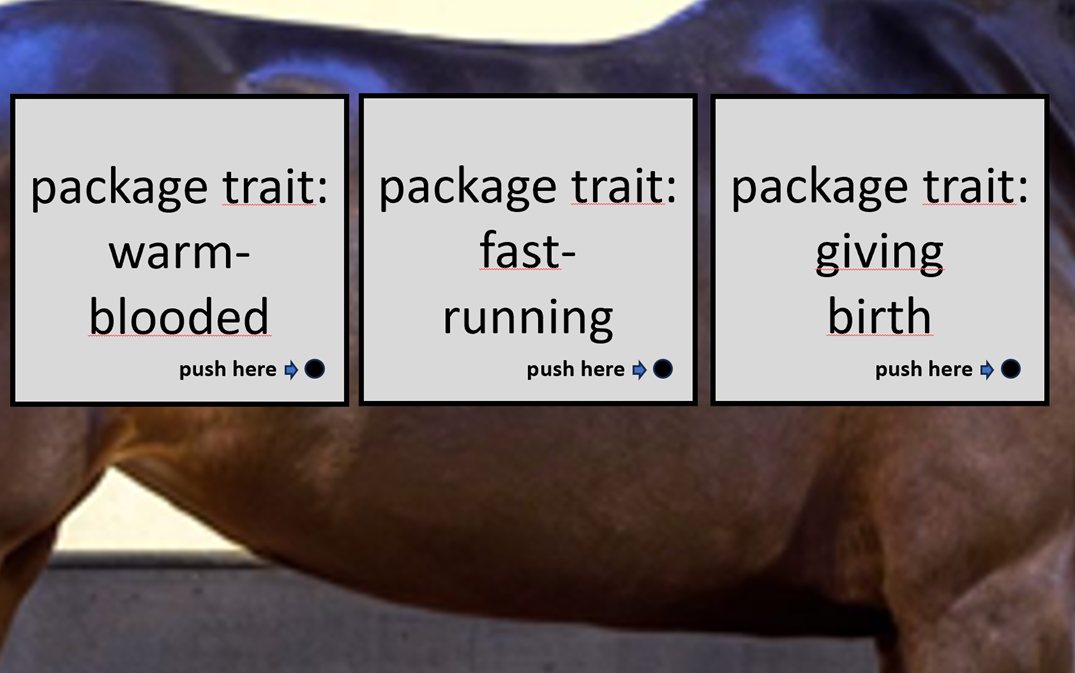

The theory presented here is that the these kinds of processes can be split in a few mayor steps that each on its own results in a viable result (or at least not a mortal result). Not a ‘survival of the fittest’ but a fit that is good enough to survive. So let’s take a look at the switch from ‘laying eggs’ to giving birth’. It is imaginable that this process happened in the following mayor steps:

- ‘Laying eggs only’ switching to the capability of laying eggs and giving birth.

- Laying eggs switching to laying eggs in combination with suckling.

- Giving birth in combination with suckling (end result)

The first step could be from ‘laying eggs’ to 1. and second step from 1. to 3. Or the first step could be from ‘laying eggs’ to 2. and the second step from 2. to 3. It is also imaginable that ‘halfway’ there is an interaction between 1. and 2.

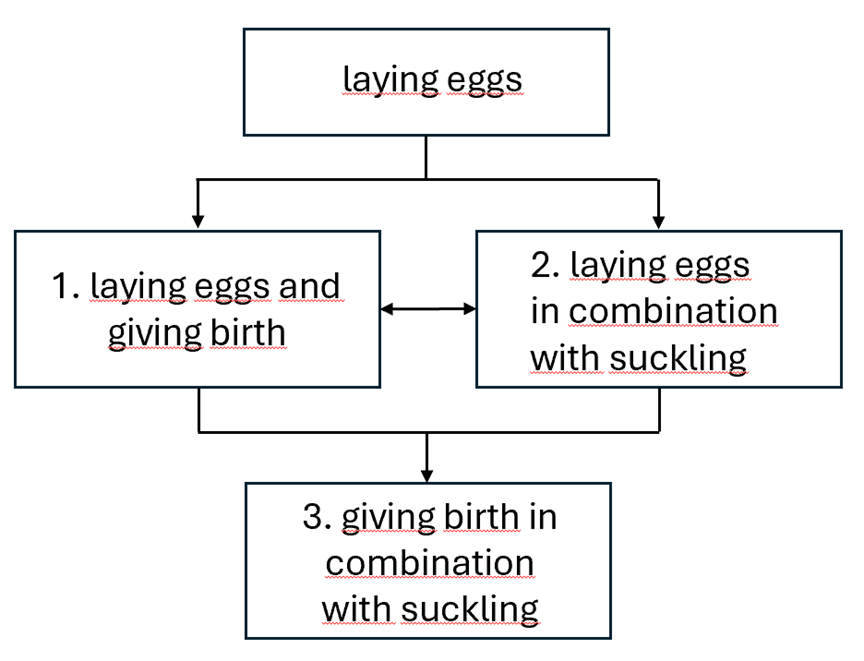

Each of these steps on their own need less mutations to complete the (partly) transition, so is more likely to happen. If indeed these intermediate results lead to a viable species (internal fit) and to another fit (‘survival of the fittest’ is no option in this situation). In the first situation (from ‘laying eggs to 1.) that should be a possibility. And indeed there are living species that have both capabilities. Different from how it works with animals which are capable of doing only one of both, but still indeed doing both separately (for instance depending on external circumstances; like water fleas and aphids). There are also animals which combine both ways, for instance by laying eggs and putting them back inside, like the echidna. The female puts the eggs in a pouch to breed them there. This is, by the way, not an animal that therefor has to be considered as an ancestor because, as I have described before, certain evolutionary processes can happen in different lineages independently from each other. According to ExT, because the basics on the concerning evolving traits are present in DNA right from the beginning. So in one lineage the process of ‘giving birth’ stopped halfway, maybe because the fit was good enough or maybe because ‘giving birth’ changed from a focused trait to a normal trait, while in other lineages this process leading to ‘giving birth’ was completely followed through, so till 3. was reached.

Laying eggs in combination with suckling does also exist (so the result of the transition from ‘laying eggs’ to 2). The most well know species is the platypus. So also a result, that in specific circumstances needs no further evolutionary steps to offer an existence but in other circumstances it does.

The above learns us that the process of ‘laying eggs’ to ‘giving birth’ can be split in two or maybe even more steps, that each on their own can give a viable result. It also learns us that traits, that look to compete with each other, can be present at the same time in own species. So indeed there can be an evolutionary slowly but surely build-up of traits, not having any (essential) function yet, but also not harming anybody. That implies that all the 50 mutations don’t need to happen during the same period in a specific order.

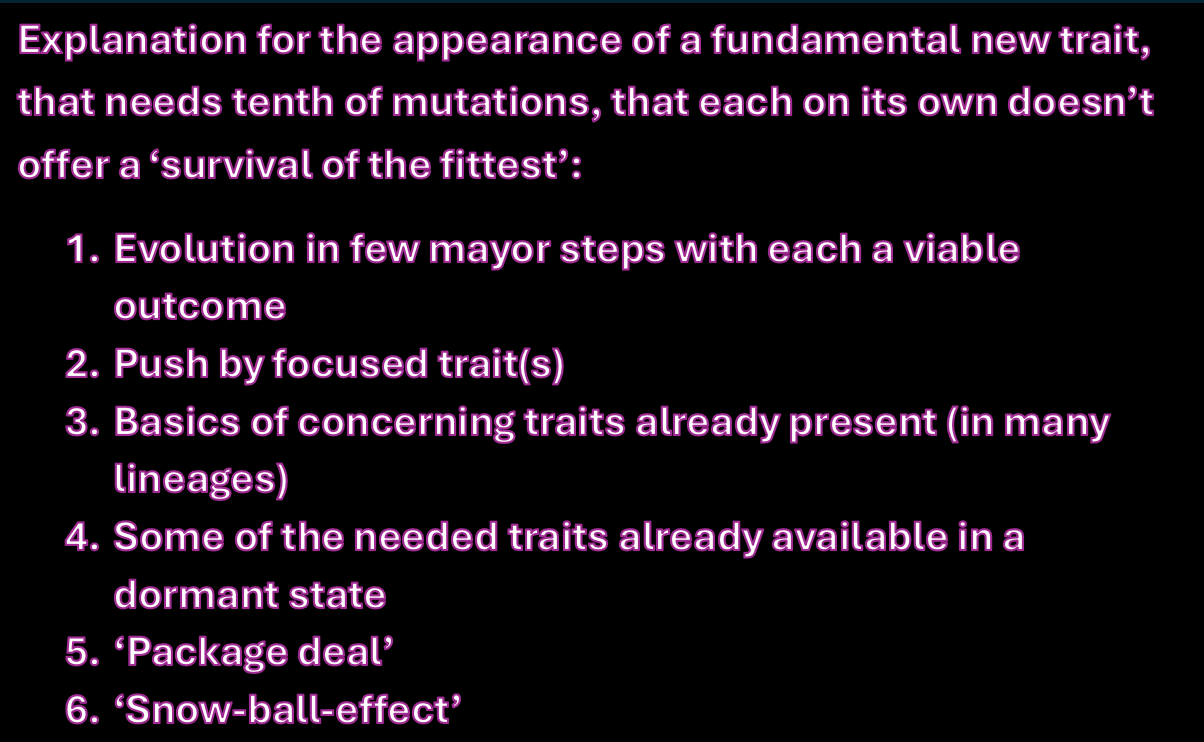

So how can NI+ExT explain an evolutionary process that demands a lot (say 50) mutations to reach the ‘needed’ end result, without the driving force of ‘survival of the fittest’ (because each mutation on its own brings nothing like that):

- The process from laying eggs to giving birth is split into a few mayor steps. Each step gives an viable result;

- Each of this steps is ‘driven’ by a focused trait;

- The basics of this trait are present in the DNA of almost all, if not all, species (in the status of a potential focused trait or as a trait, that at a certain moment during evolution switches to a potential focused trait). Also the basics of the other needed traits are already present;

- Not all the needed traits, that per main step have to be there to combine with the evolution propelled by the focused trait, have to evolve during this process. Some may already have been there for some or even for a long time, being (virtually) useless until the change to ‘giving birth’ started and was accomplished;

- Along with the process, that changes the genotype and phenotype, initiated by the focused trait, some other mutations happen. Some of them support ‘giving birth’ but some of them may hinder ‘laying eggs’;

- Some mutations concerning ‘giving birth’ initiate other mutations, also relevant for the trait of ‘giving birth’.

Contribution 4 can be seen as an accumulation process during the 100.000’s of years preceding the moment the potential focused trait ‘giving birth’ could become the focused trait ‘giving birth’ because ‘finally’ the right phenotype, that does not anymore leads to death or to nothing, but indeed to the goal of ‘giving birth’, is there.

This ‘six pack’ of contributions is in my opinion the only way to explain the evolution of a new basic trait that needs a lot of mutations. Beside that they accelerate evolution, so lead to a way faster transition and so reduce the risks of failing. This also implicates way less transition forms. So like focused traits and like revolutionary evolution this compressed process of specification produces significantly less fossils of these forms. And this corresponds with the fact that fossils of transition forms are extremely rare.

I am not the first person who presents an evolution theory based on a more directional and/or more rapid evolution. These other theories are commonly rejected by evolutionists. Sometimes with a clear motivation, but also sometimes just because of a relentless believe in Darwinism as the one and only truth. I am talking for instance about ‘Saltation’. Saltation, or abrupt specification, stands for a sudden and large mutational change from one generation to the next, potentially causing single-step speciation. Speciation, such as by polyploidy in plants, can sometimes be achieved in a single and in evolutionary terms sudden step. There were geneticists of name that supported this evolutionary concept and even Charles Darwin did not deny the possibility of genetic ‘jumps’. This mutation theory of evolution suggests that species went through periods of rapid mutation, possibly as a result of environmental stress, that could produce multiple mutations, and in some cases completely new species, in a single generation. In the 1940s a downfall of saltational views of evolution followed. But more recently these kind evolutionary theories are getting more support again. Goldschmidt (an important scientist in this respect) presented a mechanism involving “rate genes” or “controlling or regulatory genes” that change early development and thus cause large effects in the adult phenotype. Donald Prothero wrote about the importance of a few genes controlling big changes in the organisms. Embryology has shown that if you affect an entire population of developing embryos with a stress (such as a heat shock) it can cause many embryos to go through the same new pathway of embryonic development. Evolutionary biologist Olivia Judson reported in an article "Single-gene changes that confer a large adaptive value do happen: they are not rare, they are not doomed and, when competing with small-effect mutations, they tend to win. But small-effect mutations still matter a lot. They provide essential fine-tuning and sometimes pave the way for explosive evolution to follow. Goldschmidt proposed that mutations occasionally yield individuals within populations that deviate radically from the norm and referred to such individuals as "hopeful monsters". If the novel phenotypes of hopeful monsters arise under the right environmental circumstances, they may become fixed, and the population will found a new species. For example, it is clear that dramatic changes in phenotype can occur from few mutations of key developmental genes and phenotypic differences among species often map to relatively few genetic factors. Evidence of phenotypic saltation has been found in the centipede and some scientists have suggested there is evidence for independent instances of saltational evolution in sphinx moths.If you compare ‘Saltation’ with NI you see resembles and differences. Some mentioned examples, like “phenotypic saltation”, “few genes controlling big changes”, “if you affect an entire population (….) it can cause many embryos to go through the same new pathway of embryonic development”, "Single-gene changes that confer a large adaptive value do happen” and “If the novel phenotypes of hopeful monsters arise under the right environmental circumstances, they may become fixed, and the population will found a new species” do fit well into NI. The few genes or single gene are or is the focused trait(s) and one gene-mutation can cause the described snow-ball-effect. That stress can cause many of the exposed embryos to change in the same direction points in de direction of an active susceptibility and also a revolutionary evolution. And the sudden appearance of a new species under the right circumstances is of course synonym with reaching an internal and external fit.Also this sentence is relevant: But small-effect mutations still matter a lot. They provide essential fine-tuning and sometimes pave the way for explosive evolution to follow. I think this is a possibility but I think the fine tuning concerning the small-effect mutations already have taken place (as dormant traits) before the determining few genes or single gene mutate. Because reaching ‘harmony’ asks for long process of tuning and fine-tuning, which looks according to me not to correspond with saltation.The main difference between Saltation and NI is the fact that the first one is really about a dramatic change of the phenotype where NI is about a ‘dramatic’ change of the genotype that as a result in time can lead to a gradually developing phenotype but also to a more ‘dramatic’ developing phenotype. But according the Saltation that is something happening on its own while according to NI this has to do with reaching an internal fit that can more of less suddenly present itself as new phenotype.

Another evolution theory bult upon the possibility of a way faster evolution than according to the Evolution Theory, is ‘Quantum evolution’. It involves a drastic shift in the adaptive zones of certain classes of animals. The word "quantum" refers to an "all-or-none reaction", where transitional forms are particularly unstable, and thereby perish rapidly and completely.

As indicated before, during the phase, that the new focused trait is not yet there (or not able) to initiate the evolution of the concerning new species, the ancestors of this ‘new species to be’ can accumulate some traits without any (decisive) function yet. In this period of ‘waiting’, different individuals of these ancestors will have different mutations and so partly different ‘useless’ new traits. The longer this build-up of ‘useless’ (but not harming) traits, the more variations are to be expected of the new species if ‘finally’ the potential focused trait indeed becomes a focused trait, because the right internal conditions are there to reach ‘harmony’ and so an ‘internal fit’. Also ‘survival of the fittest’ will determine if indeed the moment is there for the new focused trait to show itself in the biosphere.

I will illustrate this with an example, indeed again ‘birds’. The focused trait of flying was there already for a long time, but the individuals within the family of the ancestors of birds, which started to get wings, were not able to get off from the ground because they were too heavy. And so they (probably) died. So the waiting was for a lower weight. Reading in scientific articles that this losing of weight happened very rapidly, in an evolutionary context, this ‘losing weight’ could also have been a potential focused trait. And not only that, but even a focused trait because ‘losing weight’ was not blocked by any obstructive trait. But still this process of losing weight took tenth of thousands if not hundreds of thousands of years. During this period in different individuals or groups all kinds of other mutations happened (maybe only by coincidence). So the ancestors of birds did split in all kind of subspecies (indeed fossils of different transition forms have been found). But all with the two mentioned (potential) focused traits coded in their DNA (wings and ‘losing weight’). At different moments, but probably not that far apart, in a subspecies the weight had reduced enough to make it possible to get off the ground as soon as in an individual or in a group the potential trait of flying could convert into the trait of flying (wings!). The result of this was that birds appeared in many variations. So this huge number of different birds is not (only) the result of evolutionary processes during the existence of birds but (also) the result of revolutionary processes in the ancestors in the period before birds appeared. By the way: useless does not mean by definition ‘no use’ but can also mean that a trait had some use in the ancestors and also contributed to the capability of birds to fly.

You could wonder why there are or has been no more variations of humans in the last million years. The reason is that the potential focused trait of ‘human intelligence’ was not or way less hindered by internal and external circumstances, and so maybe in only one process this potential focused trait became a real focused trait. So the variations in humans that appeared, are probably the result of different mutations after ‘human intelligence’ became the focused trait. That could also explain that it more and more becomes clear that the differences between homo sapiens and the Neanderthals are significantly smaller than they were supposed to be and why interbreeding was no issue at all.

There are about 11.000 variations of birds and not more than 1.400 variations of bats. We have seen that feathers were already available a long time before the first birds appeared. And that this long waiting was for a lower body weight; to get rid of this body weight as obstructive trait. As explained this could explain this huge number. Bats (“Evolutionary paths vastly differ for birds”, Cornell University, 2024) had a completely different evolution. The evolution of wings and legs was tightly coupled. If there were no other obstructive traits (like too much weight) one can imagine that this simultaneous evolution reduced the time before there was harmony and so the bat appeared. This reduced time limited the number of other traits to develop. This resulted in an ancestor with less incorporated variations and so in less variations of bats.

So as a conclusion this is the relation: the more demanding a new potential focused trait in relation to internal and/or external circumstances is, the more subspecies to be expected, if finally the potential focused trait becomes a lasting focused trait.

According to the Evolution Theory there is also another way to explain the development of complex traits, where each step** **_on its own don’t offer anything like a ‘survival of the fittest’. This is called Exaptation. This means a shift in the function of a trait during evolution. Bird feathers are claimed to be a classic example. Initially they may have evolved for temperature regulation, but later were adapted for flight. When feathers were first used to aid in flight, that was an exaptive use. To be honest: I don’t believe a word of this. There does not exist one species that uses feathers just for cooling. Only birds have feathers. And so if this trait is good enough for the mentioned evolutionary process, than why was that never good enough as an end result and so was always and everywhere a further development into a bird a necessity? This is farfetched and unlikely. The length of the feathers was much longer than of the limbs. If there is a relation, than it is that during the long period that the trait of feathers could not yet be used to fly, because the weight was still too high, luckily this ‘useless’ trait could serve as a temperature regulator.

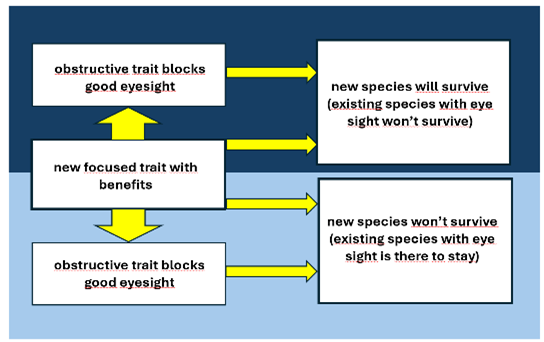

A last example of an evolutionary process, that the Evolution Theory can’t explain and NI can. The fact that some species, like some fish and beetles, loose their eyes when living in the dark. What could be the trade-off for this lost? Because having eye sight in the dark is maybe useless, but why should it make a fish with eye sight in such an environment a lesser fit? One can imagine that a change of a focused trait could also block traits that appear to be important to survive. That will inevitably lead to death unless there are circumstances that this trait is no longer essential, like eye sight in the dark. And so if a new focused trait offers a better or even a best fit in circumstances in which the negative effects of this change are not relevant anymore, the fish will have better opportunities in the dark than its counterparts with no mutation but with eye sight. If this mutation, with the side effect of losing eye sight, has also happened to fishes swimming in less dark water, we will never know that, because for them this new focused trait brings not enough compensation for losing eye sight and so is lethal.

Back to the title of this paragraph: Why are fossils of transition forms rare? There are a couple of reason why, even limited to the evolution of life. So here is a summary:

- New primary traits don’t come out of nothing but out of the already present basics of this trait as present in DNA. That implicates a kind of kick-start;

- The focused traits don’t happen randomly but with a (bit) higher frequency. This accelerates the transition process and limits the number of transition forms;

- A new species starts with a primary genetic change and so is not the result of a huge number of tiny evolutionary steps;

- In the situation of an active susceptibility the transition process could concern a group of individuals instead of a single individual. That also can give a clear acceleration of the transition process;

- Before a transition form can appear in a reasonable amount of individuals a number of internal conditions must be fulfilled (to reach ‘harmony’). These changes may be quiet subtle and so may not be visible as a transition form in fossils;

- ‘Package deals’ and ‘snowball-effects can also reduce the number of steps and so the number of transition forms.

According to some morphologists evolution happened in short, concentrated bursts. The question is, what could initiate such a burst. If a potential focused trait has found its internal fit and so becomes a focused trait, that could be the starting point of a burst in combination with the last two bullets. And the bullet above these last two, maybe supported by the first three bullets, may present the start of such a burst as an answer to external circumstances.